People of the East do not wash [= ritual immersion] after experiencing a seminal emission or after relations (since they reason that “we are in an impure land”). Residents of the Land of Israel (do wash after a seminal emission or relations, and) even on the Day of Atonement (for they maintain that those who have seen emissions should wash in secret on the Sabbath and on the Day of Atonement) as a matter of course, [which they learn] from the example of Rabbi Yosi bar Halafta, who was seen immersing himself on the Day of Atonement.

shooting from the cuff here but we all know about tebhilat ezra (discarded by the amoraim and then 'brought back' by the Kabbalists, esp. Lurianists and Chassidim). There is an article in Ta Shema (pub. Alon Shvut) about an old Minhag Ashkenaz that forbid menstruating women from attending Synagogue (perhaps an influence of MEY..). In addition you may well know that Karaites continue to be stringent about tuma'a and tahara and forbid a man who has had a seminal emission from attending the beit knesset until sundown (like sadducees I don't think they hold of 'tebhul yom' either). I can elaborate more on Karaite dinim of tuma'a and tahara if you find this subject one of interest.

11.

People of the East say that a menstruating woman may perform all types of household duties except for three things: mixing drinks, making the bed, and washing his face, hands, and legs. According to the residents of the land of Israel, she may not touch anything moist or household utensils. Only reluctantly was she permitted to even nurse her child.

I can see why Karaites made extensive use of this work. 'Wahabbi' Karaites to this day have menstruating women sit in a separate quarter, taking her meals separately from the rest of the family (well it could be worse, among the Beta Israel, the women in question is put in a special hut). A humourous anecdote from an interesting book on the matter (niddah was one of the main things that have defined egyptian karaites vis a vis their rabbanite brethren, up until the creation of the state, where a large majority turned traditional-secular)

http://books.google.co.il/books…

14.

People of the East have mourners come to the synagogue each day. Residents of the Land of Israel do not allow him to enter, with the sole exception of the Sabbath.

I did not check on current minhag but it seems to me that everyone accepted minhag babhel on this (though abhelim do usually have a minyan in their own place of residence. But I always thought that this is done for convenience sake rather because of any prohibition of an abhel to enter a Synagogue. Heck a met himself is often brought to the Synagogue to be eulogized (iirc, in EY this too was done for a great person. In addition some Cohanim would be metame themselves for a Rebbe, they considered a real 'sorva derbanan', ; the Talmidim of R Judah Hanassi is one example).

Now among contemporary Karaites, this issue continues to generate controversy. It used to be the custom that abhelim were strictly forbidden from entering their batei knesset for the duration of the shibhat yemei abhelut. Only recently has the Karaite Rabbinate (I know..Oxymoron..) introduced some leniences on the issue, especially in the case of the elderly and childless.

18.

People of the East (only) check the lungs. Residents of the Land of Israel (check) eighteen types of disqualifications.

The very stringent Hilkhot Shekhita among Karaites come to mind. More avilable upon req.

23.

People of the East will not slaughter a newly-born animal until the eighth day. Residents of the Land of Israel will slaughter even a newborn, for [they maintain that] the prohibition of the eighth day applies only to sacrifices.

On this point Karaites (and I presume other sectarians as well) diverge sharply. In fact among Karaites, it is strictly forbidden to slaughter animal before seven days have passed since its birth, following the biblical proscription of

שׁוֹר אוֹ כֶשֶׂב אוֹ עֵז כִּי יִוָּלֵד וְהָיָה שִׁבְעַת יָמִים תַּחַת אִמּוֹ וּמִיּוֹם הַשְּׁמִינִי וָהָלְאָה יֵרָצֶה לְקָרְבַּן אִשֶּׁה לַה

although one may rightfully ask that in this case Karaites are not following Biblical law to the letter (esp. the last part, as per Babhlim..).

25.

A ring does not sanctify marriage according to people of the East. Residents of the Land of Israel consider it [sufficient to] fully sanctify a marriage.

I am admittedly an am ha'aretz of the highest calbre but there seems to be much missing here. The Harei At recited when the bridegroom puts the ring on his bride's finger, what is that? merely minhag? I should think that everyone follows minhag babhel on this. If not it would make perfect sense.

Another interesting thing to note about the ring. Some Karaite purists seem to reject the entire ring ceremony (I am not sure if this is a relatively modern phenomenon or not).

there seems to be this notion that wedding rings (in general) are of idolatrous origin, I'm not sure where it comes from but this is what Karaite Hakham Qanai told me when queried on the issue "the wedding band was originally a pagan symbol (the endlessness of the risen man-god)."

See also here:

http://www.bibleviews.com/wr.html

30.

People of the East forbid bread baked by a gentile, but will consume gentile bread if a Jew threw a piece of wood into the fire. Residents of the Land of Israel forbid it (even with the wood, for the wood neither forbids nor permits. When are they lenient? In cases when there is nothing [else] to eat, and already a day or two have passed without consuming anything. It was thus permitted to revive his soul so that his soul should be maintained, but only from a [gentile] baker who has never brought meat into his bakery, even though it considered a [separate] cooked dish.)

I need to get up on my knowledge of hilkhot bishul akum but as we all know current sephardim follow beit yosef who forbids the cooking by a gentile-even if a jew is the one lighting the flame (which is ashkenazic custom of course). Now I'm not sure if andalucian Sephardim who follow Rambam are also stringent about this or not.

42.

People of the East forbid the Kohanim from blessing the congregation if they have long, unkempt hair. [Alternatively: with their heads uncovered]. Among residents of the Land of Israel Kohanim do () [in fact bless the congregation with long, unkempt hair.]

I am unsure if the intent here is to convey that in EY Cohanim actually grew their hair long or that it merely was not considered an impediment. Now we know that while the Temple stood, Cohanim were forbidden to grow their hair long and unkempt. It's interesting that davka in EY, they weren't makpid on this.

52.

(Residents of the Land of Israel permit the consumption of

daytra fats. Residents of Babylon forbid it.)

58.

People of the East fast before Purim. People of the Land of Israel [fast] after Purim, based on Nikanor. (17:4, from Tosefta)

According the JE, Anan b. David (not the founder of Karaism, but rather the founder of his own group of schismatics, instituted new fasts, one of which fell on the actual day of Purim itself!

In addition to the legal fast-days appointed by the Bible, Anan, by means of word-analogies instituted the following: The seventh day of every month; the 14th and 15th of Adar instead of the rabbinical fast of the 13th, including thus the Purim festival; also a seventy-days' fast from the 13th of Nisan to the 23d of Siwan; including Passover and Shavuot as times of fasting when neither food nor drink could be partaken of by day.

69.

People of the East do not transfer bones of the dead from little caves to small holes in caves [where presumably whole cadavers could not fit,] in order to bury other dead. People of the Land of Israel do transfer [bones]. (Rav Hai Gaon, as cited by

Ramban, in Torat ha-adam)

This is well known of course; the practice of transferring bones from a gluskema to an ossuary (and then sealed in a kukh), once the flesh was rotted. As someone who recently excavated a grave here in Israel, this is something that is of particular interest to me. What is the reasoning behind the difference among the Babhlim? Is it about kabhod hamet or perhaps that was just the custom? Also I cannot help but drop a sardonic remark about how some current residents of EY obv. follow babhli minhag on this and not at all the lenient EY one..

72.

People of the East do not mention “dew” during the summer. People of the Land of Israel do mention it. (PT Ta'anit ch. 1, Berakhot ch. 5)

Interesting that Davka Minhag Sephardim follow the EY on this.

2.

In Zoan, Egypt, which is called Fustat [today part of old Cairo], there are two synagogues: one for the people of the Land of Israel, the

al-Shamiyin congregation [=the "Yerushalmi", this name is still used today to refer to a Jewish Yemenite branch] (It is named after Elijah, of blessed memory [?, see below]). The other is the congregation of the people of Babylon, the

al-Iraqiyn congregation. They do not observe the same customs. (Selections from Yosef Sambari,

Seder HaHakhamim, Neubauer I, p. 118. On page 137 it states that the congregational synagogue then still in use was built before the destruction of the second temple in Jerusalem.) One, (the people of the Land of Israel) stands during

kedusha, while the other, (that of the residents of Babylon) sit during kedusha. (Rabbi Avraham ben HaGra,

Maspiq l'ovdei hashem.

The Al Shami'im of course refer to Damascus and mean the entire region once referred to as Coele-Syria. Minhag Eretz Yisrael is also known as 'shami' minhag. It is def. an interesting topic. I am particularly fascinated how there were EY minyanim in the lion's den itself (babhel) and conversely, Babhli minyanim in EY and other locales in the near east (as Goitien points out in his first vol. of Mediterranean Society

Which bring me to your next passage:

Margulies accepts the claims regarding the basic "Yerushalmi" orientation, but understands the purpose more subtly. Rather than taking a confrontational stance, the work merely seeks to explain and rationalize the local customs and decisions to the new Babylonian immigrants who were not aware or respectful of the locals. No attempt is made per se to reject the validity of the Babylonian customs themselves and at times the author troubles himself to explain them only.

As if it wasn't bad enough that Babhlim refused to give the Eretz Israelites the time of day on calendrical matters (see Evyatar Gaon and Pirekei Dr;' Eliezer's stern take on this specific matter), many babhlim persisted in their minhagim even after ascending to EY. This was a clear violation of following minhag hamaqom and smelled of yhara among other things. I should thing that this problem became particularly pronounced when Sura was under the kingship of Yehudai Gaon and his notorious disciple Pirkoi...

Of special interest is following the disputes from the Geonic period until the end of the period of the Rishomin signified by the publication of the Shulhan Arukh. In general, the Babylonian side prevailed as their hegemony increased, but in a number of cases, the position native to the Land of Israel in fact dominated, especially when it did not contradict any explicit statements in the Babylonian Talmud. This tradition was especially strong in Tsarfat and Ashkenaz (France and Germany) as opposed to Sepharad (Spain), which historically remained tied to the Babylonian Geonim. The influence of the Land of Israel side is especially noticed in the house of study of the great Rashi and his students

...Geographic location was clearly a major factor. In France and Provence use was much more pronounced than in Spain.

Another interesting tidbit which point to many possible connection between early Minhag Ashkenaz and Sarefat on the one hand, and Minhag EY on the other.

I can't help but quote and comment on your last part re: Minhag Ashkenaz and also Karaite usage of the book:

One reason for the neglect of this work may have been it's brevity. [For example, the usual explanation for the grouping of the twelve prophets in one scroll, and today in one volume, is so that the small books would not become lost.]

Personally I don't buy the brevity argument. Bahag is pretty brief. Sheiltot as well.

However, a more compelling reason appears to be the negative impression that the work made on certain authorities, most notably, Nahmanides, Ramban (Avodah Zara 35b). It was (correctly) perceived that the work contains material which contradicts the Babylonian Talmud, already considered supremely authoritative.

Have you had a chance to read Talya Fishman's book where she convincingly (I am..) shows that the Babylonian Talmud was from from a 'said all' until the end of the Geonic Period. Geonim themselves in their own responsa conspicuously omit mention of various gemarot. The Talmud was still seen as a book of notes and commentary, rather than a canonical work (almost on a par) with Tanakh.

Methods of study which stressed a proper historical understanding of all legal points of view would become common in rabbinic circles well before the modern period, but at the time they were not yet developed. If an opinion could not be utilized for determining the halakha, it was not deemed worthy of further inquiry. Nahmanides is the only early Spanish sage who even mentions the work, so it is not at all surprising that he considers it outside the pale of legal precedent.

Possibly, the Spanish Sages resisted the work as a result of the utility that Karaites received from it and quoted from it. They may have suspected the work of being a Karaite forgery.

This makes little sense. As I have pointed out in my previous email; many halakhot in the hilluk explicitly contradict Karaite interpretation of Halakha

In contrast, early Provencal authorities made ample use of the work. They

9. Use of the book by Karaites

Karaites took a much keener interest in the disputes than Rabbanites. This is not at all surprising. The Rabbanites claimed to possess an authoritative Talmudic tradition handed down from the earlier sages. Every known dispute amongst the Talmudic sages themselves was utilized in order to argue against these claims. From Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai to disputes amongst the Babylonian Geonim themselves, the Karaites seized upon the disputes between East and West eagerly.

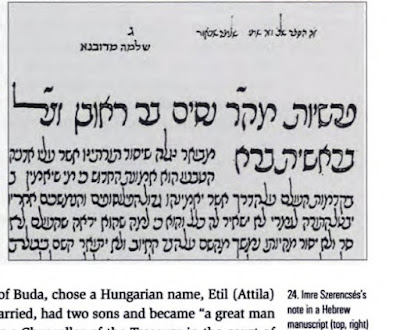

The first Karaite sage to quote the work is

Jacob Qirqisani

(10th century). Since he cites the work in an overtly apologetic manner (read: missionary), he was wont to exaggerate and even forge sections of the work. Thus, it goes without saying that his work cannot be utilized uncritically. Nevertheless, despite this cautionary note, his early explanations can at times be very useful in understanding the nature of the disputes themselves.

He explains his interest in the disputes very clearly. According to him, the disputes between East and West were more extensive than the disputes between the Rabbanites and the Karaites,

An odd claim...

but nevertheless, claims of heresy were never leveled and a spirit of tolerance reigned between the communities. So too, the Karaites should be accepted by the Rabbanites .

This brings to mind a passage from the famous epistle from Sahl b. Mazliah Hacohen cited in Nemoy's Karaite Anthology where he points out the Rabbanites of EY were very conciliatory toward many of his positions (!)

"Sahl was especially interested in calendric questions, and in one of his writings reviews the whole controversy between Rabbi Meïr of Jerusalem and Saadia in order to draw attention to the conciliatory disposition of the Palestinian Jews"

s a dispute which Qirqisani appears to have invented out of whole cloth, an out and our forgery not attested to in any other versions of the work:

“People of Babylon do not permit one to betrothe a woman with [the fruit of] the seventh year. People of the Land of Israel permit this. Therefore, the betrothals of that year in the Land of Israel are not considered by the Babylonians to effect marriage, and their children are not valid.”

[According to Mordekhai Akiva Friedman (Madaei HaYahadut 31), a maculation of

taba'at

to

shevi'it

resulting from graphic similarity between the letters

tet

and

shin

From Qiqisani's time on, Karaites have continued to utilize the work in their own disputations with Rabbanites. As we saw earlier, this may have led to the work's falling out of favor among Rabbanites in regions where Karaites were active.