Are The Greeks Still Nursing a Grudge Against Jews for Chanukah?

It’s September in Sparta, and the merciless Mediterranean sun beats down on the assembled crowd. The observer picks up a mingling of Greek and Hebrew words and phrases. Pleasantries are exchanged, with promises to keep in touch and strengthen cooperation and friendship and the like. This conference, titled SPARTA-ISRAEL CONFERENCE 2018: Renewing an Ancient Friendship, took place this previous September and was organized by the Greek branch of the fraternal B’nai Brith Organization.

The advertisers of this conference drew on history and current geopolitical realities to encourage an alliance between modern-day Jews and Greeks. The choice of Sparta as the location for this conference may have been deliberate. The brochure reads:

“At about 300 BC, a wise and long-reigning leader, King Areus of Sparta, sent a letter to the High Priests of Jerusalem addressing them as brothers and proposing a friendly alliance between the two peoples. The Areus initiative and ensuing consistent events are recorded in the Book of the Maccabees and the History of the Jewish People by the historian Josephus Flavius. Following the strong and long-standing symbolism of the above, the Sparta-Israel Forum aims to further promote Hellenic-Israeli cooperation within a worldwide horizon and toward the mutual benefit of the two historical peoples.”

What are these mentioned letters all about?

In the ancient Second Book of Maccabees, Chapter 12, verse 20–23 there is an interesting passage:

“Arius, king of the Spartans, sends greetings to Onias (Chonyo), the chief priest. It has been found in a writing concerning the Spartans and Jews that they are a kinsmen, and that they are descended from Abraham. Now since we have learned this, please write us about your welfare. We for our part write you that your cattle and property are ours and ours are yours. So we command them to report to you to this effect.”

Josephus also quotes this letter and also records correspondence between the Spartans and both Simon the Hasmonean and his brother Jonathan.

The current geopolitical realities that are seeing warming ties between the Jewish state and its non-Arab neighbors in the Mediterranean is not without its detractors. Some Greeks are still nursing a grudge against the Jews, it would seem.

In 2014, the Greek Political Party Syriza bumped one of its candidates, Theodoros Karypidis, after the latter alleged that “Nerit”, the acronym of Greece’s new public broadcaster, was derived from the Hebrew word for candle, which he linked to the Jewish festival of Chanukah, which commemorates the struggle of the Maccabees against the Greeks. He then lashed out against the Greek government. “Samaras [the then Greek prime minister] is lighting the candles in the seven-branched candelabra of the Jews,” Karypidis wrote on his Facebook page, adding that Samaras was “organizing a new Hanukkah against the Greeks.”

One of the delicious ironies about Chanukah is that the aforementioned Books of Maccabees form part of the Greek Orthodox canon (as well as that of other Christian denominations). This is astounding when one recalls that the Jews did not preserve those books at all (in fact, all current editions are re-translations from Koine Greek. However, it is also important to note that some rabbis — such as the former Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Israel Mordechai Eliyahu — strongly encouraged the reading of the Books of Maccabees on Chanukah).

The Greek Orthodox Church also celebrates a Chanukkah of sorts of their own, the commemoration of the “Maccabean martyrs” takes place on August 1. The Church also considers Antiochus Epiphanes to have been an impious pagan.

As Jon D. Levenson wrote several years ago in an article in the Wall Street Journal:

“And so we encounter another oddity of Hanukkah: Jews know the fuller history of the holiday because Christians preserved the books that the Jews themselves lost. In a further twist, Jews in the Middle Ages encountered the story of the martyred mother and her seven sons anew in Christian literature and once again placed it in the time of the Maccabees.”

It is important to note that paganism and worship of Greek gods did survive in Greece up until modern times. In fact, these modern-day Zeus worshipping Greeks- calling themselves “Supreme Council of Ethnic Hellenes”- have experienced a renaissance as of late. They are not looked at with sympathy by most Greeks to be sure; in 2017 the BBC quoted Officials of the Orthodox Church who condemned the neo-pagan movement as “a handful of miserable resuscitators of a degenerate dead religion”.

The relationship between Jews and Greece and Greek culture is complicated and nuanced. For instance, I find it ironic that there are only two orthographically kosher languages in which one can write a Torah scroll according to the Halacha: Ashurit (Assyrian script) and Greek. This is quite a remarkable thing, a Torah scroll written in ancient Paleo-Hebrew is invalid (perhaps there’s also an anti-Samaritan polemic hidden there).

It’s important to remember that Chanukah was not and is not an anti-Hellenistic Greek holiday it is also interesting to note that Greek Jews strategically translate “the wicked Greek kingdom,” which appears in the Al Hanisim prayer, into “The Syrian kingdom,” which is technically correct and also spares them a PR headache.

Professor Devin Naar, a scion of Salonikan Sephardim and historian of Balkan Sephardic Jewry writes:

Jewish leaders in Salonica published a new prayer book, Sha’are Tefilah, in March 1941. One of the pioneers in the field of the Sephardic Studies in the United States, the Istanbul-born and Seattle-based writer Albert Adatto acquired an exemplar of this rare book, thereby enabling us to access the long-lost world of Jewish Greece on the brink of destruction.

Remarkably, the editors of the prayer book — Salonican-born Jews who had been educated in Palestine — dedicated it to a Jewish soldier who had fallen on the battlefield defending “our beloved homeland, Greece.” Written not in Greek, but rather in Judeo-Spanish, the dedication aimed to show to Jews themselves that they ought to think of themselves not only as religiously Jewish and culturally Sephardi, but as Greek patriots, too. They believed that all of these allegiances could be held simultaneously.

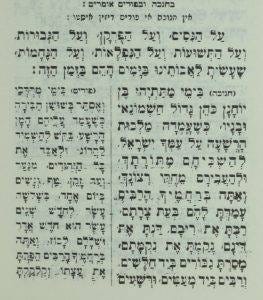

The Al ha-nissim prayer from Siddur Sha’are Tefilah. It omits the standard reference to the “wicked Hellenic government.” (ST00348)

But in order to accommodate their Jewish and Greek identities, they made two noteworthy changes to the prayer book. In the Al ha-Nissim prayer added to the Hanukkah liturgy that refers to the miracles associated with the holiday, the traditional reference to the “wicked Hellenic government” is quietly changed to the “wicked government.”

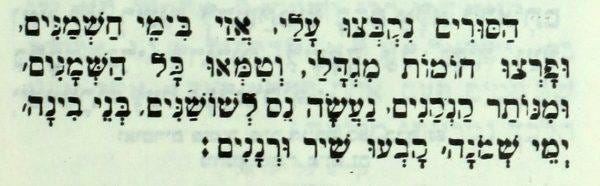

More remarkably, in Maoz tzur (“Rock of Ages”), the popular Hanukkah song, the reference to the enemy as Yevanim (“Greeks”) is replaced by Suriim (“Syrians”). The editors accomplished this clever switch by reference to the historical record. The Seleucids, the Hellenistic empire in control of Judea at the time of the Maccabees, were indeed culturally Greek, but they were geographically based in Syria. Hence the Salonican Jewish leaders could transform the “Syrians” into the Hanukah enemies and thereby more easily embrace Greece as their beloved homeland.

The rabbis adopted a very nuanced attitude toward Hellenism throughout the Greco-Roman period. Many rabbis, beginning from the Mishnaic era, adopted Greek names, co-opted many Greek ideas and even praised the wisdom and beauty of the Greeks in their homiletic teachings.

The early rabbinic writings have only tender things to say about Alexander the Great. You may be familiar with the famous story of the Jewish High Priest going to meet the mighty general as the latter planned an invasion of Judea (this appears both in the Talmud and in Josephus with slight variations). The province of Judea, or “Coele-Syria,” switched hands several times after Alexander’s untimely demise. Whether under the Ptolemaic-Egyptians or the Seleucid-Syrians, there was little persecution under Alexander’s early generals/successors, and in fact, Antiochus I (ancestor of Antiochus Epiphanes- “the mad one”) was a Philosemite by all accounts.