What happened to the Sephardic community in German Danzig in the early part of the 17th century?

See my latest at the Jewish Link https://jewishlink.news/features/48862-avraham-the-wanderer

לְמַעַן יֵדְעוּ דּוֹר אַחֲרוֹן בָּנִים יִוָּלֵדוּ יָקֻמו וִיסַפְּרוּ לִבְנֵיהֶם -תהילים עח That the generation to come might know them, even the children that should be born; who should arise and tell them to their children- Pslams 78

See my latest at the Jewish Link https://jewishlink.news/features/48862-avraham-the-wanderer

This post will continue on theme of a previous post where I discussed how Chassidim switched from the Ashkenazic rite to a modified Sephardic rite.

Rabbi Nathan Adler of Frankfurt, Germany (one of the mentors of Rabbi Moses Sofer known as the Chatam Sofer) was another Ashkenazic Jew who switched from nusach ashkenaz to nusach sefard under the influence of Lurianic Kaballah. However- unlike the Eastern European Chassidim- he also switched to the Sephardic pronunciation of Hebrew (H.Z. Zimmels hypothesized that the Chassidim did not switch to the Sephardic pronunciation because it would have been too difficult for them. Adler reportedly had a Sephardic scholar living in his house for over a year in order to teach him the "proper" pronunciation of Hebrew see here).

This post will continue on theme of a previous post where I discussed how Chassidim switched from the Ashkenazic rite to a modified Sephardic rite.

Rabbi Nathan Adler of Frankfurt, Germany (one of the mentors of Rabbi Moses Sofer known as the Chatam Sofer) was another Ashkenazic Jew who switched from nusach ashkenaz to nusach sefard under the influence of Lurianic Kaballah. However- unlike the Eastern European Chassidim- he also switched to the Sephardic pronunciation of Hebrew (H.Z. Zimmels hypothesized that the Chassidim did not switch to the Sephardic pronunciation because it would have been too difficult for them. Adler reportedly had a Sephardic scholar living in his house for over a year in order to teach him the "proper" pronunciation of Hebrew see here).

In the last 2 decades of the 18th century, concurrent with the rise of the hassidic movement in eastern Europe, a pietist group was emerging in

Dubnow doubted the existence of a direct link between the formation of adler’s circle and the emergence of Hasidism, and most other scholars who have considered the question agree. Some reconsideration of this position is now required, as the scholarly world has recently revised its view of the spiritual nature of early hassidism and embarked on a new assesement of its religious and social features. The new approach ..studies the beginning of hassidism in the context of the religious awakening then taking place in the world of kabbalistically oriented pietistic groups active in 18th century

See Hatam Sofer, Responsa, Orah hayyim, para. 15: “therefore my master, the wise, pious, and priestly Nathan Adler, f blessed memory, he would himself lead the services and pray in Sephardic pronunciation from R’ Yitzchak Luria’s prayer book.” Cf. Abraham Lowenstein of

Before the end of the century, the myth of sephardi superiority was widely disseminated and available for appropriation by Jews and their enemies alike…in their battle against racial myths about jewish deformities, jewish anthropologists drew on the Sephardi mystique to create a countermyth of their own- that of the well-bred, aesthetically attractive, physically graceful Sephardi, a model of racial nobility and virtue. In their work John efron notes, “the Sephardi served as the equivelant of the Jewish ‘Aryan’…the physical counterpart to the ignoble Jew of Central and Eastern Europe.

Todd endelman pp. 31-32

With the advent of emancipation in central

Schorsch p. 71

..there is little doubt that beyond the worldwide influence of Lurianic Kabbalah, the religious culture of Spanish Jewry held but slight allurement for a self-sufficient and self-

Confident Ashkenazi Judaism in its age of spiritual ascendancy.

Schorch p. 72

Nafatali herz wessely, whose admiration for the Sephardim of Amsterdam was born of personal experience, had contended in the fourth and final letter of his Words of Peace and Truth that the Sephardic pronunciation of Hebrew was grammatically preferable to the manner in which the Ashkenazim rendered it. A generation later, the teachers and preachers who pioneered the development of a German rite adopted the Sephardic pronunciation for their “German synagogue”. Not a point of Hakachic contention, the switch could be defended by Eliezer Liebermann in terms of grammatical propriety or by Moses Kunitz of Ofen (buda) in terms of demography- more than seven eighths of the Jewish world offers its prayers in the Hebrew of the Sephardim but the ultimate motivation of this unnatural and self conscious appropriation of Sephardic Hebrew was the desire to extinguish the sound of the sacred tongue from that of Yiddish, which these alienated Ashkenazic intellectuals regarded as a non-language that epitomized the abysmal state of Jewish culture.

Schorsch 77

Mayer Kayserling born in

Schorsch 85

It should be noted that the close resemblance in pronunciation between the biblical Hebrew taught at German universities of the time and the Hebrew of the Sephardim no doubt bestowed a verisimilitude of correctness of the latter. ..In a most interesting letter dated 4th October 1827, J.J. Bellerman, a well known theologian, scholar and director of the prestigious Berlin Gymnasium advised Zunz to teach the youngsters in the Jewish communal school over which Zunz presided the Sephardic pronunciation of Hebrew from the very beginning. Bellerman had been invited to observe a public examination of the children. While expressing his pleasure at the event, he did see fit to challenge the retention of the “Polish pronunciation of Hebrew,” because it managed to offend both the vowels and accents of the language. And in conjunction with the vowels, he pointed out the historical superiority of Sephardic Hebrew,

As you well know the writings of learned Alexandrian Jews—in the Septuagint, Josephus, Philo and

Quoted in schorch p. 89-90

Some Ashkenazi rabbis were actually of the opinion that praying with the Sephardic pronunciation rendered the prayers null. The latter were particularly incensed by the failure of the sephardim to distinguish between a patach and a kametz [2]. (the Chazon Ish held that the Sephardim mispronounce gods name and it should be adoinoi [as in oy] rather than adonay [as in aye]. Zionism and the Rebirth of Hebrew Eliezer ben Yehuda was impressed with the pronunciation of the Sephardi community in Palestine and their pronunciation was adopted but not without controversy. The poet Yehoash mentioned how strange the Sephardic Hebrew sounded to him when he settled in Rechovot shortly before World War I. In 1890 he helped create the Hebrew Language Council ( Va'ad Ha Leshon Ha Ivrit) whose stated purpose was to disseminate works in Hebrew and establish Hebrew as the official language of the Yishuv.Although modern Hebrew is similar to the Sephardic pronunciation, it isn’t exactly alike. For instance, Sephardic Hebrew differentiates between an ayin and an alef, as well as between a chet and a khaf while modern Hebrew does not do so in both cases.

During Ben Yehudas visit to Morroco, he met a maskil by the name of Abraham Moshe Luntz who conversed with him in Sephardi-accented Hebrew and informed him that this was the language that united the various different communities in the yishuv. Ben-yehuda Hahalom veshivro 11

Subsequently after that meeting ben yehuda sailed to

Although ben –yehuda was not a religious Jew, he dressed as a traditional Sephardic jew, grew a beard and regularly attended the local synagogue hahalom veshivro 107

It wasn’t long however until he managed to arouse the ire of the Jerusalem Sephardic rabbinate who responded with 3 seperate bans against his and his his newspaper “Hatzvi”.

Ben yehuda particularly disliked the Sephardic chief rabbi yaakov shaul elyashar because he considered him be from the old generation of jews who were stuck in the galut mentality. He did however form close ties with elyashar’s succesro, Yaakov Meir who was highly sympathetic to ben yehuda’s ambitions ad the former was instrumental in introducing the modern Hebrew language into the schools of the Sephardic community in

Ben yehuda’s close friend david yudilevitz describes how the rewners of the Hebrew language discussed the practiality of introdcing modern Hebrew as the lingua franca of the residents of the yishuv:

On the outskirts of

“To revive the language, very well, but how shall we go about it” the elder of the group began.

“very simple, all the schools will be established and those that are already in existence are incumbent to teach the Hebrew language as a living language. The students will be obligated to converse only in Hebrew whether they are in schoolm at home and in the synagogue

His disciple joseph klauner writes that the reason ben yehida chose the Sephardic pronunciation was because this was the pronunciation used by Christian when transliterating the ancient Hebrew names into their own languages see klausner, joseph Mifal hayyav.

A meeting of the Hebrew Teachers Association in 1895 adopted Hebrew as the language of instruction, with Sephardic pronunciation to be used (but Ashkenazic pronunciation was allowed in the first year in Ashkenazic schools, and for prayer and ritual). The next meeting of the association was not until 1903, at the closeof a major convention of Jews of the Yishuv called in Zikhron Yaakov by Ussishkin, the Russian Zionist leader. The 59 members present accepted Hebrew as the medium of instruction…and there was general agreement also on the use of Ashkenazi script and Sephardic prounication.

By Roger Friedland, Richard D. Hecht p. 58

In the “high Ashkenazi” ,for instance, o is said instead of a and au instead o, and in certain positions, like at the end of a word, the letter tav is pronounced as an s instead of a t. They also stress syllables differently. Thus the first words of the bible are read Bereshit bara Elohim in the Sephardi and Boreishis boro Elauhim in the Ashkenazi pronunciation…In Hungary there was an attempt to introduce Sephardi pronunciation already in the 19th century. Following German examples, it was Moses ben Menachem Kunitz (1774-1837) of Obuda, the Rabbi of the Buda community from 1828 until his death, author of some valuable Talmudic works, a Zohar analaysis, (ben Yohai, 1815), and even a drama in Hebrew verse (Beit Rabbi, 1805), who in 1818 published a Rabbinic decision (pesak) which announced that the Sephardi pronunciation should be used in the synagogue instead of the Ashkenazi one. His main argument was that seven eighths of the world’s Jews prayed using the Sephardi pronunciation (this figure was obviously exaggerated). Kunitzer was in favor of reforms in general; he even supported the efforts of Aron Chorin. He studied in

The activity of Kunitzer had no real result, but in spite of its failure, it indicates that representatives of the haskalah were unanimously convinvced that the Sephardi pronunciation preserved by certain isolated Jewish groups throughout centuries, was closer to the original sound of the Hebrew language than the Ashkenazi one, the common language of European Jews altered under german influence. JEWISH BUDAPEST PP. 457-458

In the first half of the 19th century, when various movements called for the reformation of Jewish life were developing, the Sephardi culture seemed a real alternative to for Ashkenazi jewry. It appeared to be a means to overcome the Asheknazi heritage which they regarded as backward…In contrast with the 16th century..at that time Ashkenazi culture enjoyed higher status, since Ashkenazi jews had not converted to any other religion, had bnot become marranos. Around 1500 when the first scholarly Hebrew grammar books were published in Europe, the authors naturally took the language of Jews living in

Jewish

…In the 1950s, the leadership of the Hungarian jewish community strictly forbade the Sephardi pronunciation which sounded similar to Modern Hebrew. It was even forbidden at the Rabbinical Seminary, lest they be accused of Zionism and thus invite political or police intervention. Those who study Hebrew these days may learn both pronunciations, yet the attraction and impact of the Israeli intonation is powerful. In Synagogues, the Ashkenazi pronunciation is still in use, but younger people, including students of the Rabbinical Seminary, switch to the Sephardi-Israeli reading they became accustomed to during their stay in

Ibid p. 461

Mayer Kayserling (1829-1905) a german born historian and Rabbi of Budapest. He is best known for his pioneering studies of the history of the Sephardim and crypto-jews. In his works, Kayserling betrays an unmistakable pro-Sephardi bias, contrasting the “lowly” language and manner of the Ashkenazic Jew with the “nobility of character” and “purity of the language” of the Sephardic Jew. He also naturally felt that the Sephardic pronunciation of Hebrew was the correct one.

Quoted in efron scientific racism pp. 86-87

Notes: 1. see for instance Ismar Schorsch, "The Myth of Sephardi Supremacy," reproduced in his From Text to Context: The Turn to History in Modern Judaism (Hanover, N.H., 1994), (also in Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 34), Benjamin Disraeli and the myth of Sephardi superiority Journal Jewish History Issue Volume 10, Number 2 / September, 1996 The Noble Sephardi and the Degenerate Ashkenazi, 2. see for instance Meshichei Hasheker Umitnagdayam by Benyamin Hamburger regarding the early 18th century false messiah Löbele Prossnitz.

It was Memorial Day 1984.

My grandfather was sitting at the desk in his small sefarim filled study, at my grandparents’ Highland Park, New Jersey,

home, working on the budget of the yeshivah elementary

school he’d founded 39 years earlier. Back then much

courage had been needed to start a yeshivah.

Today it is hard for us to grasp the intense opposition

there was to yeshivah education in this country just two

or three generations ago. Opposition from Yidden who

were members of Orthodox shuls! My Jersey hometown

was typical. When my grandfather wanted to start a

kindergarten and first grade, few of his baalei batim had any

interest in sending their kids to a yeshivah for elementary

school. Many more were hostile to the very concept.

In 1945 when my grandfather planned to open the

yeshivah, American patriotism was at its height. The

United States had just saved the world from Nazism. It was

considered very “American” to send your children to the

then-excellent public schools. American Jews desperately

wanted to fit into the monolithic American culture. Sending

your kid to yeshivah was definitely not “fitting in.”

To give an example of how weak Yiddishkeit used to be in

this country, in 1930 over 4,000,000 Jews lived in the United

States. Yet when Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchak Elchanan in

New York City needed a new ninth-grade Rebbi, it sponsored

my grandfather’s immigration from Lithuania to fill the job.

There were no American-born mechanchim at the time.

Rebbeim had to be brought over from Europe.

Baruch Hashem, it was hashgachah that saved my

grandfather when he came to the United States from

Lita. No one in his family back in Lithuania survived the

Holocaust. Neither, to the best of my knowledge, did any of

his chaverim from his years learning in Telshe under Harav

Yosef Leib Bloch survive Operation Barbarossa.

After coming here my grandfather married my

grandmother, the American-born daughter of a Telshe

family, and in 1938 accepted a position in the Rabbanus. He

became the Chief Rabbi of New Brunswick, New Jersey.

While there were lots of families in the kehillah, it must

have been difficult to become the Rav of a community with

very few learned — let alone shomer Shabbos — baalei batim.

My grandfather saw what a catastrophe public school

education was for the local Jewish youth. Plus, he needed

a yeshivah for my uncle, who was entering first grade. So

he founded Moriah Yeshiva Academy* in New Brunswick

for the school year starting in September 1945. Though it

consumed most of his time over the next 40 years, my grandfather never took a salary from the yeshivah, nor does my family own the building.

On that warm spring morning exactly 35 years ago, my

grandfather suffered a heart attack. He called out to my

grandmother in the next room to dial 911. While waiting for

the ambulance to arrive, he suffered a second heart attack.

In the ambulance, on the 1.5-mile ride to Middlesex County

Hospital in New Brunswick (since renamed the Robert

Wood Johnson University Medical Center), my grandfather

suffered a third heart attack. Things looked ominous. He

asked my grandmother to call their children to the hospital,

then said, “Nu, ich hob nit kein taynes tzu G-tt” (Nu, I have no complaints to G-d.)

My parents, uncles and aunts quickly came to the

hospital. The doctors were performing the new procedure

of angioplasty on my grandfather. They allowed only one

family member to come into the room every half-hour or

so. As soon as a relative came in to see my grandfather, he

would ask him or her, “What time is it?”

As if it mattered.

But my grandfather asked for the time at 5:00, 5:30, 6:00,

6:30, and so on.

“What time is it?”

“Five to nine.”

“Good, it’s late enough. Now we can count Sefirah.”

My grandfather recited out loud, “Baruch Atah, Hashem,

Elokeinu Melech Ha’olam asher kideshanu b’mitzvosav

v’tzivanu al Sefiras HaOmer...” (pause) “Hayom shnayim

v’arba’im yom shehem shishah shavuos baOmer (Today is

42 days, which are six weeks in the Omer)...” My grandfather

then closed his eyes and shortly thereafter returned his

neshamah to his Creator.

May we all be zocheh to have an appreciation such as his

for the mitzvah of Sefiras HaOmer.

* MYA subsequently moved to Edison, N.J., and was later renamed the Rabbi Pesach Raymon Yeshiva. Several thousand Jewish children received their Torah education at the yeshivah my grandfather founded 74 years ago.

Jewish leaders in Salonica published a new prayer book, Sha’are Tefilah, in March 1941. One of the pioneers in the field of the Sephardic Studies in the United States, the Istanbul-born and Seattle-based writer Albert Adatto acquired an exemplar of this rare book, thereby enabling us to access the long-lost world of Jewish Greece on the brink of destruction.

Remarkably, the editors of the prayer book — Salonican-born Jews who had been educated in Palestine — dedicated it to a Jewish soldier who had fallen on the battlefield defending “our beloved homeland, Greece.” Written not in Greek, but rather in Judeo-Spanish, the dedication aimed to show to Jews themselves that they ought to think of themselves not only as religiously Jewish and culturally Sephardi, but as Greek patriots, too. They believed that all of these allegiances could be held simultaneously.

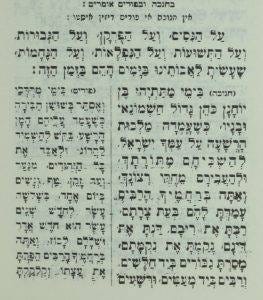

The Al ha-nissim prayer from Siddur Sha’are Tefilah. It omits the standard reference to the “wicked Hellenic government.” (ST00348)

But in order to accommodate their Jewish and Greek identities, they made two noteworthy changes to the prayer book. In the Al ha-Nissim prayer added to the Hanukkah liturgy that refers to the miracles associated with the holiday, the traditional reference to the “wicked Hellenic government” is quietly changed to the “wicked government.”

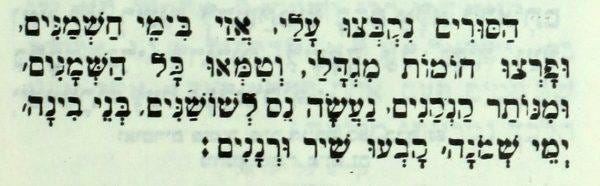

More remarkably, in Maoz tzur (“Rock of Ages”), the popular Hanukkah song, the reference to the enemy as Yevanim (“Greeks”) is replaced by Suriim (“Syrians”). The editors accomplished this clever switch by reference to the historical record. The Seleucids, the Hellenistic empire in control of Judea at the time of the Maccabees, were indeed culturally Greek, but they were geographically based in Syria. Hence the Salonican Jewish leaders could transform the “Syrians” into the Hanukah enemies and thereby more easily embrace Greece as their beloved homeland.

at my other blog